Records show that since 2015, ICE has requested face recognition scans of DMV databases in at least 14 states. That includes the DMV databases of Alaska, Arizona, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Maryland, Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Utah, Vermont, Washington and Wisconsin. (As of the publication of this report, Colorado, Illinois, Maryland, Utah, Vermont and Washington have since prohibited DMV compliance with ICE face recognition requests for civil immigration enforcement purposes.) Furthermore, as described in Finding 1, ICE also held a contract with the Rhode Island DMV for access to its face recognition database. Combined, this suggests that ICE agents and DMV officials acting on ICE’s behalf have used face recognition technology to scan the faces of at least 83 million drivers. This includes about 1 in 3 adults in the U.S.

Those searches easily constitute a dragnet. When ICE, and DMV officials on its behalf, use face recognition to search a state’s license photograph database, everyone’s image is being scanned by ICE, not just those of the person under investigation. In Wisconsin, one ICE agent conducting an identity fraud investigation requested a face recognition comparison against Wisconsin’s database of 4.3 million driver’s license photographs. In Georgia, another ICE agent repeatedly requested face recognition comparisons of an individual’s photographs against Georgia’s collection of 7.3 million driver’s license photographs.

ICE’s use of face recognition may result in misidentifications and false arrests. According to peer-reviewed research by scholars Joy Buolamwini, Timnit Gebru and others, face analysis algorithms often underperform when analyzing the faces of women, young people and people with darker skin tones. Those bias problems extend to facial comparison systems and may worsen when state DMVs use antiquated face recognition systems—as is sometimes the case.

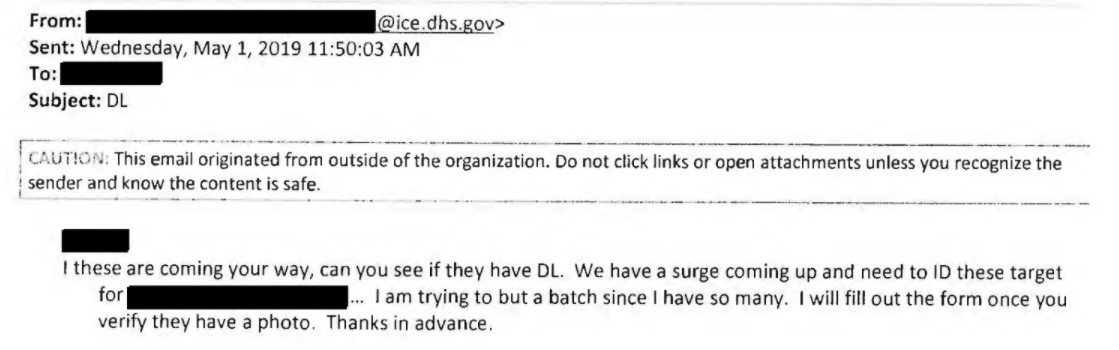

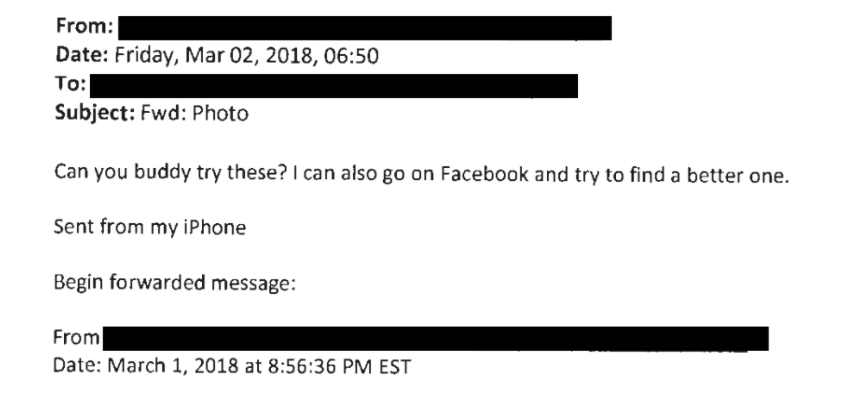

There are few regulations limiting law enforcement’s use of face recognition generally and almost no regulations addressing ICE’s use of the technology. While courts have yet to rule on the constitutionality of face recognition in the law enforcement context, several scholars have raised concerns about its legality under various constitutional provisions, especially the First and Fourth Amendments, and it is unclear whether the practice is even legally authorized in the first place. Since at least May 2020, ICE policy has claimed to prohibit the use of face recognition technology by its ERO division for civil immigration enforcement purposes. However, as a practical matter, there is no sharp line separating ICE ERO’s enforcement of civil immigration law from the operations of ICE’s Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) department, which is charged with investigating criminal activity. When ICE HSI conducts criminal investigations, its efforts routinely lead to “collateral arrests” of people who were not the original targets of the investigation. As a result, even if those arrests constitute civil immigration enforcement, the investigations who led to them may be exempt from ICE’s stated bar on face recognition.

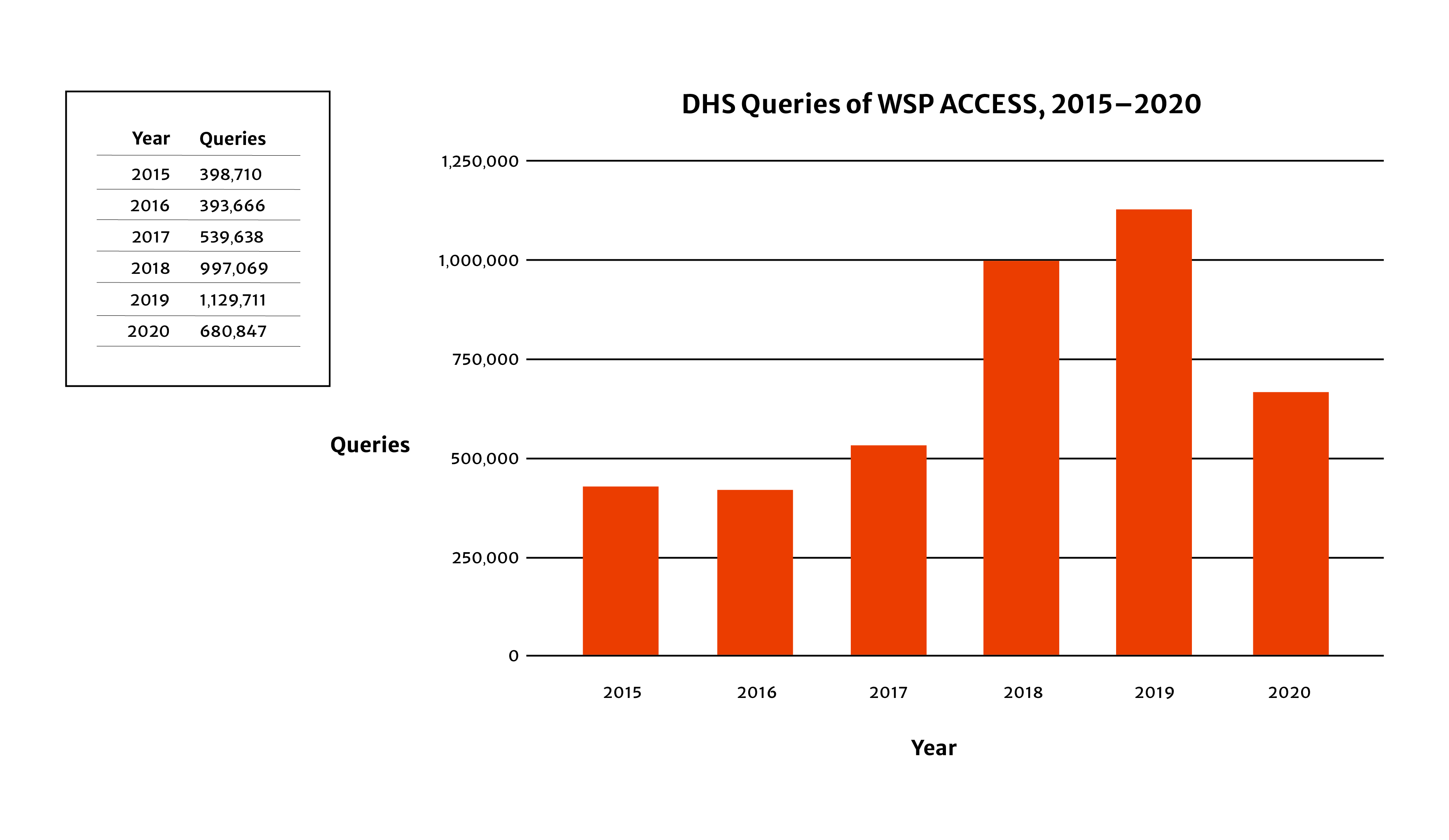

ICE has shrouded its use of face recognition technology on state driver’s photos in a level of secrecy more similar to what one would expect from a federal agency whose primary purpose is large-scale surveillance than from an agency that claims to be engaged in law enforcement. The FBI, one of the nation’s most powerful law enforcement agencies, has disclosed the list of each state DMV it has relied on for face recognition searches. It has also disclosed the memorandums of agreement underlying those efforts and has for years publicized statistics about its use of its own face recognition system, the Next Generation Identification (NGI) Interstate Photo System (IPS), on a monthly basis. Similarly, CBP has disclosed where each of its border face recognition systems has been deployed along with each of the photo databases it has relied on for face recognition searches, regularly publishing the number of face recognition searches it has conducted.